What can we learn from pillboxes?

29/05/2020 | Chris Kolonko

Let’s take a look at a wartime pillbox from home.

During the COVID-19 pandemic please do not visit the coast unless you live there. We encourage you to enjoy the coastline digitally, through our website and social media.

On the 30th of May 1940, during the height of Operation Dynamo (The Dunkirk evacuation), Commander in Chief of Home Forces General Ironside issued orders for the commencement of construction of defences within his anti-invasion defence scheme (Dobinson, 1996. pp. 26). Reconnaissance of beaches had started a week earlier on 24 May 1940.

Ironside’s plan called for the fortification of the coast, known as the Coastal Crust, along the East, South and West coasts. It wasn’t the first anti-invasion scheme, fortification of London and sections of the East coast had been undertaken under the command of Ironside’s predecessor, General Kirke, but this was the first time an extensive plan was put in motion.

Ironside’s defensive plan focussed on a series of stoplines focussed on the coast (the Coastal Crust), secondary stoplines at strategic points across the country, and the GHQ line; the final line of resistance and point from where the mobile GHQ reserve would be deployed. Among these stoplines were nodal points, consisting of defended towns, villages, bridges, and river crossings.

Ironside’s scheme was short-lived. Ironside was replaced as Commander in Chief of Home Forces by General Alan Brooke in mid-July, and as Ironside’s plan started to near completion in August 1940 the defensive strategy was changed significantly by Brooke, which did away with the stoplines established under Ironside. But that’s another story. The Coastal Crust defences and the strategy employed remained very much the same, but defences were revised, consolidated and improved extensively between 1940 and 1942.

A key component of the Coastal Crust defences was the pillbox. Possibly the most recognised remaining feature of the 1940s defences, the pillbox today represents only a fraction of the defences constructed in the coastal and intertidal zone. Pillboxes are often seen in isolation today and are poorly investigated and understood as a result. In reality pillboxes would be surrounded by barbed wire, trenches and also subject to detailed plans for troop distributions and plans if an invasion force landed. Little of these left a mark on the landscape and today are all but forgotten.

This blog will look at what we can learn from surviving wartime pillboxes and what we can record (when it’s safe to do so again) to ensure their preservation by record.

Many pillboxes look the same, but there are many often subtle but important differences that go un-noticed and unrecorded. Essentially each pillbox was unique in terms of its deployment in the landscape and construction.

Although pillboxes and other surviving wartime defences should always be considered and interpreted as part of a wider defensive landscape, this blog will look at what we can learn by looking at and recording a single pillbox. There is also a handy recording guide that can be used for recording pillboxes through CITiZAN when we can get back to the coast.

Changes in defensive strategy and doctrine saw pillbox construction officially halted in February 1942, though construction and use in many commands had finished towards the latter half of 1941. Pillboxes were constructed over a period of just 20 months from June 1940, with most constructed during the first 16 weeks of this period (Dobinson, 1996) for use by the Regular Army. After pillboxes became obsolete, trench based defended localities and strongpoints took precedence, until the point when anti-invasion defences were stood down and demolished between 1942-44.

The Pillbox

So, what can we learn by taking a look at this pillbox and what do CITiZAN record when surveying these structures?

The aim of a survey is to create an accurate record of the structure to ensure preservation by record and also aid to future interpretation.

This is ‘Earwig Villa’ which can be found on the East Yorkshire coast. This Second World War pillbox has been the focal point of much of our fieldwork at Auburn Sands, where some of the best preserved Coastal Crust defences survive in Yorkshire.

Let’s have a look at what we’ve learned about this fun pillbox and what we record.

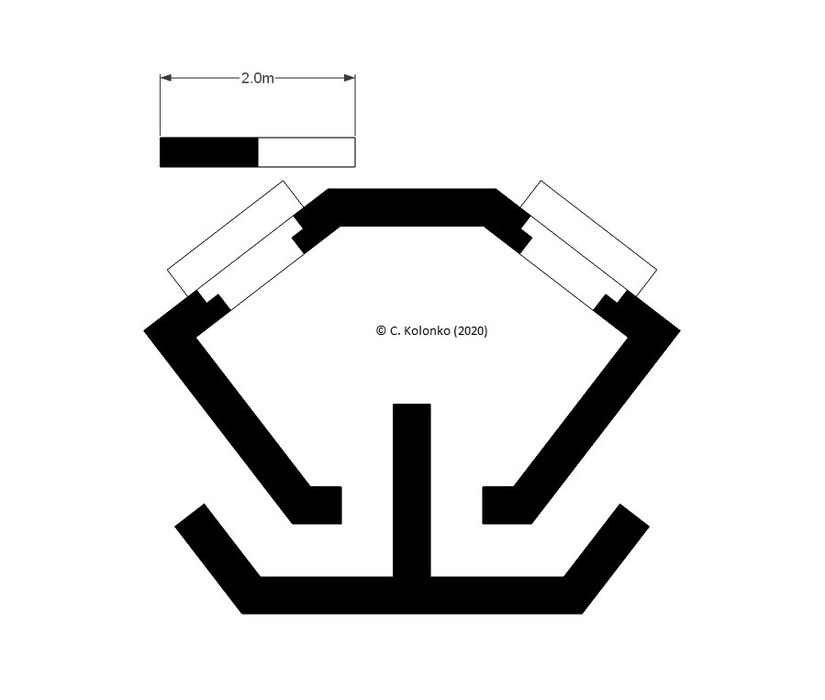

Shape in Plan

When recording wartime pillboxes, we start with the most basic aspect of the structure’s form- its shape in plan. Although this is very basic information, it can tell us a lot about the structure and its function. Also, if the only viable form of preservation is preservation by record, we need to know what shape the structure is if it can’t be preserved physically. It is often difficult to record a pillbox’s shape in plan through photographs alone unless they are visible from above.

In this case, Earwig Villa is a complex irregular hexagon in plan. This description can be supported by a basic sketch or scaled plan like this one. Creating a plan is very useful when dealing with complex shapes like that of Earwig Villa.

Orientation

It might not seem obvious or important but recording the direction a pillbox faces also tells us a lot. If you look through many records for wartime pillboxes, you will see that many don’t include this simple but vital piece of information. If a pillbox is lost, we won’t know which way it faced.

Recording the direction a pillbox faces (its orientation) can tell us a lot about the pillbox; such as the expected direction of advance of invading forces, as well as what key strategic points in the landscape the pillbox was sited to cover.

The direction a pillbox faces is usually opposite the structure’s entrance.

But with Earwig Villa’s localised pillbox design, the entrances face diagonally forward, which makes interpretating the orientation awkward but this can be easily overcome by making further observations. By looking at the embrasures, we can work out which way the pillbox was orientated. This pillbox faces East, or would have done before it started to slump due to coastal erosion. We’ll take a closer look at why the pillbox faces East later.

Wall thickness

Yes, wall thickness. It may seem minor but again, measuring and recording the thickness of a pillbox’s walls tells us a lot.

Here’s why it is important. Pillboxes were constructed to two specifications: bulletproof and shellproof (Dobinson, 1996. pp. 38). These wall thicknesses were recommended by the Department of Fortifications and Works (DFW) and were the basis for the pillbox drawings issued by DFW Branch 3.

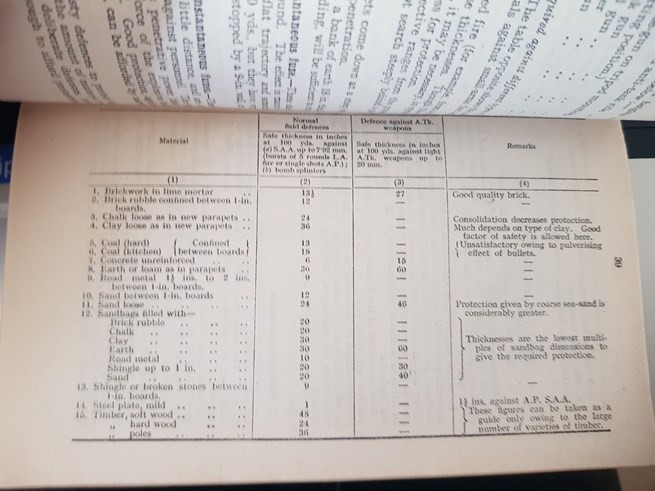

During the Second World War, a wall thickness of 0.38m (1ft 2in) of reinforced concrete was considered bulletproof, while a thickness of 1.06m (3ft 6in) was considered shellproof. First World War era pillboxes often have a much thinner wall thickness and at the time of writing no documents relating to standard wall thickness specifications have been found.

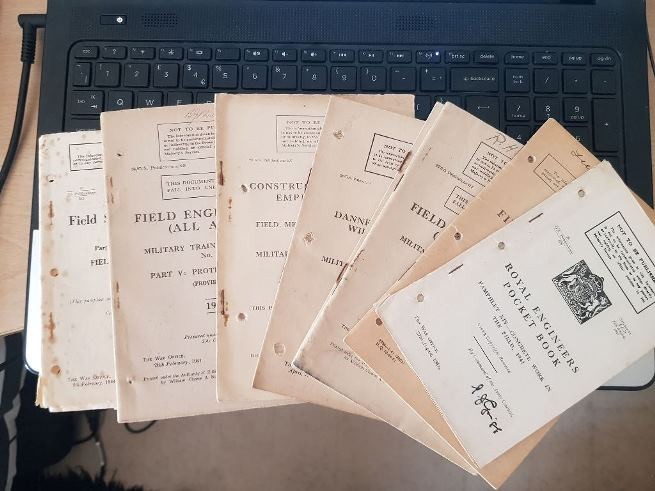

Quick note, wartime manuals are also key to assessing wartime defences. The Royal Engineers recommended specific thicknesses for different materials and an example of a Protection Table can be found in the snappily titled 1941 training manual ‘Field Engineering (All Arms) Military Training Pamphlet No. 30. Part V: Protective Works’ (War Office, 1941 pp.39).

The documentary record clearly shows that pillboxes were recorded and catalogued by the military based on whether they were bulletproof or shellproof. Information regarding the progress of pillbox construction and resources used/needed was recorded by all commands on a weekly basis and that information sent on to allow assessment of construction progress to be conducted (Dobinson, 1996). The myth that ‘records weren’t kept because pillboxes were built too quickly’ still pervades today despite being completely untrue.

Recording wall thickness can also be used as an indicator of what resistance the pillbox was expected to come up against. Pillboxes with shellproof walls were expected to come up against heavy resistance, possibly in the form of tanks or supporting field artillery.

Earwig Villa’s walls are exactly 0.38m thick, showing us the pillbox was constructed to bulletproof standard. A full survey of the structure in the future will be conducted to identify if this wall thickness is consistent across the entirety of the structure. This tells us that this pillbox was expected to come under small arms fire and the reinforced concrete walls were constructed accordingly to protect the crew.

Right, so now we know the pillbox’s shape, which way it faces and how thick its walls are. What next?

Number of Embrasures and their Orientations

Embrasures are the holes in the walls of pillboxes used for firing weapons.

When recording pillboxes it is vitally important to record the orientations of embrasures. This is rarely recorded and as such when pillboxes are lost we have no idea which direction they faced and which directions their embrasures pointed, making it impossible to assess the effectiveness of the wartime defensive landscape.

To do this we can use cardinal points (North, East, South West), intercardinal/ordinal points (North-East, South-West etc) or compass bearings (180 degrees). If possible, it is useful to assess the arc of fire provided by the embrasures. In a lot of cases the, embrasures were designed to allow a 60 degree arc of fire (30 degrees each side of the centre line).

Earwig Villa has two embrasures wide embrasures, one in the North-East facing elevation and one in the South-East facing elevation. These embrasures appear to have been designed for a tripod mounted Medium Machine Gun, most likely the Vickers, and would have provided a relatively wide arc of fire of between 60 to 90 degrees. Although the structure is slumping due to coastal erosion, it appears to be on its original alignment. The sides of the embrasures are also stepped to try and minimise the threat of projectiles being funnelled into the pillbox’s interior.

The projections below the embrasures on the exterior are hollow on the inside and would have been used to accommodate the forward legs of the Vickers tripod. These examples feature an in the field modification can be seen on their lower extent. This chipped out recess was carried out to accept the forward leg of the machine gun tripod in use, either to increase the arc of fire or to accept the tripod of the Bren Light Machine Gun. Experimental archaeology and reconstruction, as well as documentary research will help us reach the right conclusion in the future.

The embrasures also retain painted range information above. This information would have helped the machine gunners within the pillbox assess the range to targets on the beach, allowing them to fire more accurately.

A further feature associated with the firing of machine guns can also be found on the roof of the pillbox in the form of four pipe lined holes. These were used to vent the propellant gasses created by firing of the guns from within the pillbox.

The Anti-Ricochet Wall

You will often find a wall built within a pillbox. This wall is known as an ‘anti-ricochet wall’. As the name suggests it was designed to reduce ricochets, namely bullets and splinters/fragmentation that entered the interior of the pillbox. The wall also offered some protection from grenades lobbed into the pillbox, but if the enemy had got close enough to throw grenade into the structure the troops inside were as good as dead.

Recording the shape and thickness of the wall is useful as it allows us to visualise and assess the internal configuration of the structure.

Earwig Villa is, again, an exception to the norm. It features a very short bullet-proof wall attached to the ceiling of the structure. But why? Space inside the pillbox is very limited. As the pillbox had the potential to house a pair of Vickers medium machine guns, their crews, ammunition and supplies, space was a much needed commodity. A full length wall would have bisected the interior and taken up much needed space. The short anti-ricochet wall was a compromise, while reducing the protection of the crew, increased the space they had to operate in.

Surrounding Defensive Features

Although coastal erosion has destroyed much of the surrounding landscape, making it impossible to identify supporting earthworks such as weapon slits and trenches, there are some notable defensive features in the vicinity.

The most obvious feature is the anti-tank wall found in front of the pillbox. No need to explain its function but the relationship between the two structures is very important. Although both have shifted significantly due to coastal erosion the surviving features indicated that the anti-tank wall was constructed butting the pillbox. It is likely that the spur of the wall was originally in line with the base of the pillbox, possibly as a way of reinforcing the base against undermining by tidal action and ensuring that movement of the pillbox did not affect its arcs of fire over time.

Defensive Landscape Context

Context is everything in archaeology and this is no different when recording and attempting to understand modern archaeology, such as wartime defences. Without this context these structures mean very little.

When recording wartime defences, such as pillboxes, it is key to identify the function of the structure we are recording, identify what its purpose was within the local defensive framework and understand how it was located in the landscape to carry out this purpose; namely to bring fire to bear on the surrounding area or specific points within that landscape.

Without this context the structures are almost devoid of any meaning and local, and potentially national, significance cannot be assessed or appreciated.

So what can we learn from Earwig Villa? Quite a lot!

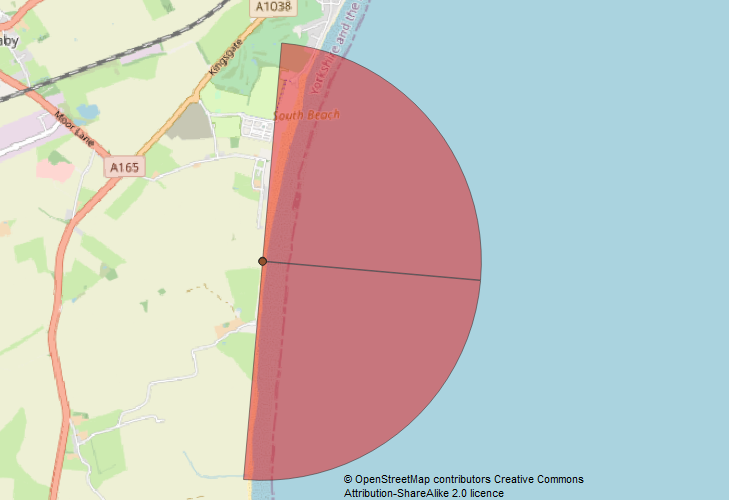

Let’s start by looking at its location. The pillbox is located here on the beach. You can take a look around using the map below-

First things first, we can see that the pillbox sits above the high water mark on a large expanse of beach. This being a pillbox of the Coastal Crust that makes perfect sense.

The embrasures are orientated to facilitate fire in enfilade, which is fire along the longest arc of a target, in this case the beach. This allowed the guns within the pillbox to cover a larger area. At low tide this would have meant that most of the beach would be covered by effective fire.

Earwig Villa was also clearly sited to cover the anti-tank obstacles, including the anti-tank wall and nearby anti-tank cubes. Covering these obstacles with effective fire was basic military defensive doctrine and key to ensuring that the obstacles weren’t breached.

So to conclude, Earwig Villa was sited within the landscape to cover the open expanse of beach with effective fire and also cover the anti-tank obstacles located on the beach.

A more in depth look at the wider defensive context of Earwig Villa can be found here- citizan.org.uk/blog/2018/Dec/14/wartime-defences-auburn-sands/

But why is it called ‘Earwig Villa’?

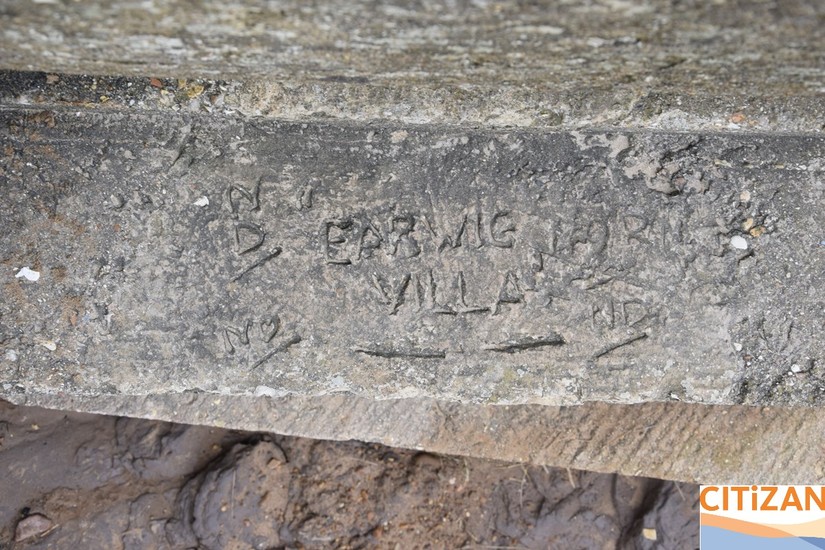

Finally, where did Earwig Villa get its name? This is really simple to answer!

There is some period graffiti to be found below the North-East facing embrasure. This reads ‘Earwig Villa’. This was clearly incised into the still wet concrete, possibly by a civilian contractor or soldier of the Royal Engineers, likely the former.

What next?

Once it’s safe to do so after COVID restrictions are lifted you may want to record a pillbox for CITiZAN. This handy guide can be used during this recording.

medialibrary/2020/05/How_To_Record_Pillboxes_v2.pdf (CITiZAN)

Also, you can help us to record wartime defences from the comfort of your own home. Check out getting involved with our Armchair Archaeology project. More details here- citizan.org.uk/blog/2020/May/01/armchair-archaeology-citizan/

You can also investigate the Yorkshire medium machine gun pillbox further from the comfort of your own home with this 3D model.

Bibliography

Dobinson, C.S., 1996. Twentieth Century Fortifications in England Volume II: Anti-Invasion defences of WWII. Council for British Archaeology.

War Office, 1941. Field Engineering (All Arms) Military Training Pamphlet No. 30. Part V: Protective Works (Provisional). HMSO

Brigham, T, Buglass, J. and George, R 2008. Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment. Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. Bempton to Donna Nook. EH Report No. 235. Kingston-upon-Hull: Humber Archaeology