The forgotten sounds of Joss Bay

04/10/2022 | Lawrence Northall

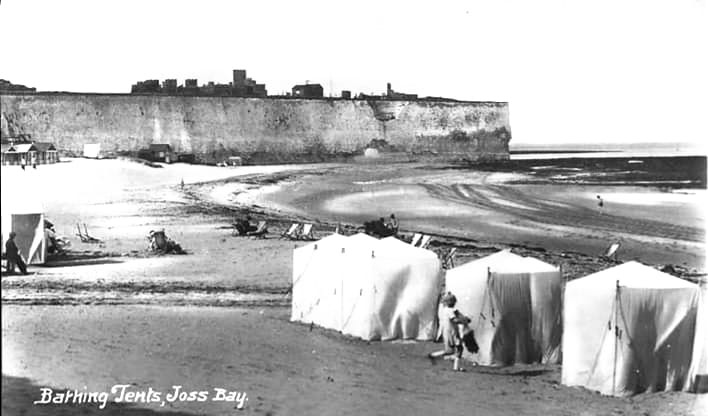

Early 20th century postcards show a long history of holidaymaking in Joss Bay, one of a series of picturesque beaches reaching around the northeastern tip of Kent. Close to North Foreland lighthouse, the bay has a wide view of the open sea from sands sheltered by chalk cliffs, providing a desirable location for beach huts in the past and, no doubt, many an afternoon in the sun.

Joss Bay in the early 20th century

However, in 1918 the area became home to a research station that conducted a secret programme of acoustic trials under the guidance of Major Wiliam Sansome Tucker, an imaginative and ambitious advocate of sound as a military resource and tool of defence. Just north of the beach huts a station HQ would soon appear, resembling little more than a shed adorned with sandbags. The nearby cliffs would provide a well orientated catchment area for sound sources originating near northern France, and the stage would be set for a series of sonic experiments that ranged from the innovative to bizarre.

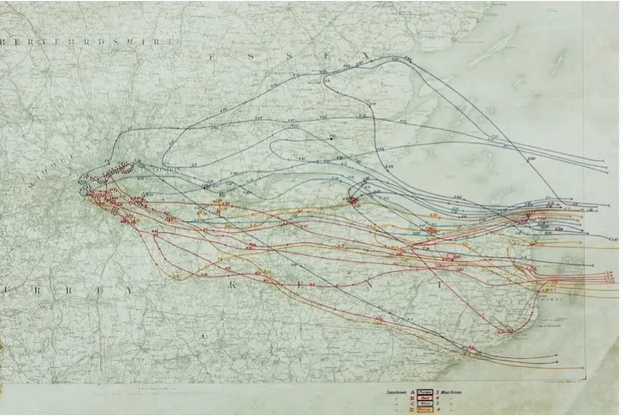

Map showing German flight paths in the First World War (image source)

Despite the unusual nature of the work carried out at Joss Bay, there’s almost no trace of the station or public recognition of its history today, even though its later home at Hythe is commemorated by information boards and a miniature interactive sound mirror. However, with recent work by CITiZAN revealing new evidence to suggest at least some remains of the station may survive, there could be hope of a raised public profile for this once important centre of military acoustic detection.

An unusual feature and possibly the last tangible connection to Tuckers research station in Joss Bay (CITiZAN)

Acoustic detection and sound mirrors

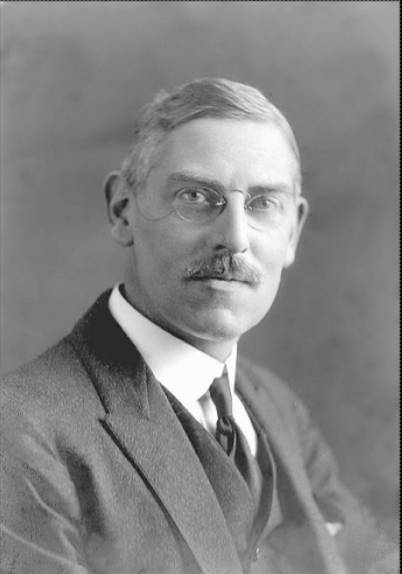

Major William Sansome Tucker (Scarth 2017, pg 3)

No wonder there was a great deal of military interest in Tucker’s research proposals, which drew on systems he’d helped to advance on the western front. Of particular importance had been his invention of the hot wire microphone, which recorded enemy artillery firing sounds and enabled the British to establish their positions, by coordinating readings from multiple locations. Building on the work of future Nobel Prize winner Lawrence Bragg, this development in sound ranging put Tucker at the forefront of military acoustics. Using listening devices to forewarn of approaching sounds wasn’t completely new though - the Royal Engineers had been attempting to use portable sound collectors to enhance their hearingsince 1914. However, these small and peculiar looking devices weren’t large enough to accommodate the physics of low frequency engine noises, which accompanied the dreaded approach of Gotha bombers and German airships.

(Scarth 2017, pg 207)

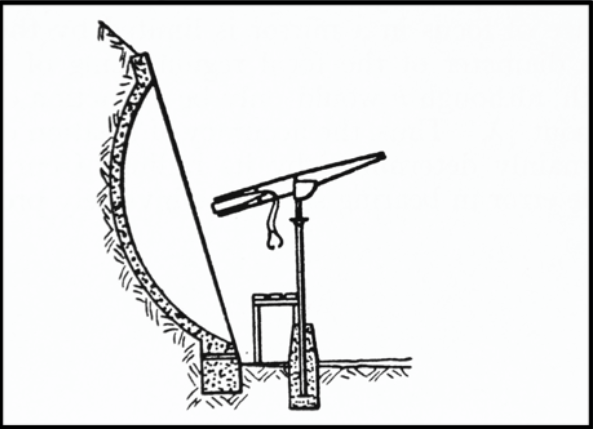

Two different examples of sound collectors, used by the Royal Engineers for enhancing listening (Scarth 2017, pg. 22)

In 1915 a stationary, fifteen-foot concave dish was carved into chalk near Maidestone in Kent, with the aim of harnessing lower frequency sounds. Built to the dimensions of a small spherical section, the geometry of the shape meant soundwaves would reflect inwards, concentrating near a central point. The exact focal point changed depending on which areas of the mirror face the soundwaves struck, meaning the listener could approximate the direction of a sound source by establishing the loudest point in the focal area. The results of the tests were encouraging enough that more research was deemed valuable.

The first sound mirror, built at Binbury Manor in 1915 (Scarth 2017, pg. 22)

Cross section showing spherical sound mirror (Scarth 2017, pg. 32)

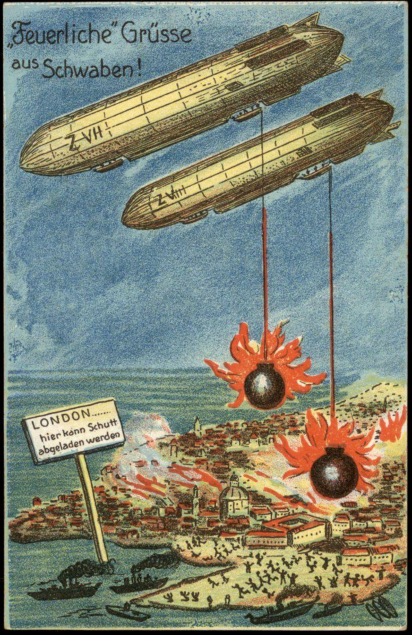

The first operational sound mirror isn’t certain, but it’s likely to have been the earlier of two surviving at Fan Bay, above the cliffs of Dover. Also carved from chalk, this mirror was surfaced in a concrete slip, to maximise its reflectiveness, and may have been the first to ‘see action’ (with forewarnings of enemy aircraft documented in October 1917). What followed was a wave of sound mirror construction, mostly in the northeast of England and Kent, which included one at Joss Bay capable of matching readings with Fan Bay. These comparisons allowed the establishment of cross bearings on incoming sounds, providing a more precise estimate on aircraft (or seacraft) location. However, the truth is that the sound mirrors were not hugely effective. Giving a forewarning of only 15 minutes at the very best, it’s likely their drive was in part politically motivated, in order to appear active against a wave of previously unknown and devastating air-raids, that were plunging the nation into narratives of fear.

German zeppelin propoganda poster from the First World War, the sign reads 'unload debris here' (image source)

Acoustic research in Joss Bay

The establishment of a dedicated acoustic research station at Joss Bay in 1918 is indicative of the seriousness that was given to the role of sound in military applications at this time. As well as improving the efficacy of listening methods within the mirror there, by pioneering the use of microphones in a listening instrument, a range of other techniques for both acoustic detection and projection started to be investigated.

The sound mirror at Joss Bay with listening apparatus, including a stethoscope (Scarth 2017, pg. 42)

Following a sound installation and exhibition on Kent’s coastal sound mirrors at the Ramsgate Festival of Sound in 2020, CITiZAN ran an event which saw volunteers help to record an unusual feature in the northern cliffs of the bay, originally spotted by CITiZAN in 2018 and only recently accessible thanks to a tall mounting bank of sand abutting the cliff.

Volunteers help to record a feature in Joss Bay in 2020 (CITiZAN)

The team drew measured plans and took photographs of the remains, to establish if they matched up with surviving images of an unusual horizontal disc experiment. It was decided that they were most likely the last trace of this strange undertaking, which sought to enhance the listenability of sounds by isolating them behind a giant wooden circle that could be maneuvered on a vertical plane.

Photograph showing the acoustic disc experiment at Joss Bay with research headquarters visible in the background (Scarth 2017 pg. 182)

The same principle had been applied in trials near London, where round pits were dug, and microphones placed beneath them at strategic locations. A large disc over the pit had helped to separate the sounds of aircraft from commonplace noises, which were registered by the microphone and fed back to a central headquarters. With each pit represented by a light on a map, observers would be able to see an aircraft approaching as the various microphones triggered their lights on and off while the sound passed. The image is one of a primitive radar screen, with a crude rendition of movement produced by a panel of small bulbs.

Acoustic disc trial at Hendon aerodrome in 1918 (Scarth 2017, pg. 150)

Even more unconventional was Tuckers’ use of large metal pipes. Installed in a tower just south of Joss Bay, these were tuned to the resonances of specific engine sounds and would start to vibrate at their frequencies sooner than the human ear could notice them. The work built on a similar idea pioneered in the front-line earlier in the war, when a piano was carefully tuned to the frequencies of German aeroplanes. However, this novel attempt to forewarn of enemy activity was foiled, when the adapted piano was captured by the, presumably bemused, enemy in an advance.

Another idea developed in the bay incorporated the use of parabolas, geometrically harmonious cone-like instruments that could concentrate sound into a kind of beam. Using sound generators, these fired acoustic signals out to lightships in the North Sea and tried to establish if they could be aimed and received accurately. If successful it was thought they could enable aircraft to land in fog, helping them position themselves in relation to an unapparent airfield by aligning to columns of sound.

Bowl shaped sound mirror constructed at Hythe after the station's move from Thanet (Scarth 2017, pg. 92)

A move to Hythe

By 1921 activities at Joss Bay were winding down. With fewer aircraft passing this stretch of coast in peacetime and acoustic research still blossoming, it was decided an alternative home should be found. Military land near Hythe lay on active civilian flightpaths and was chosen as the new base for a substantial research facility in 1922. Here the dimensions and effectiveness of larger 20ft sound mirrors were refined, before the most ambitious of Tucker’s project yet began in earnest along the coast at Dungeness.

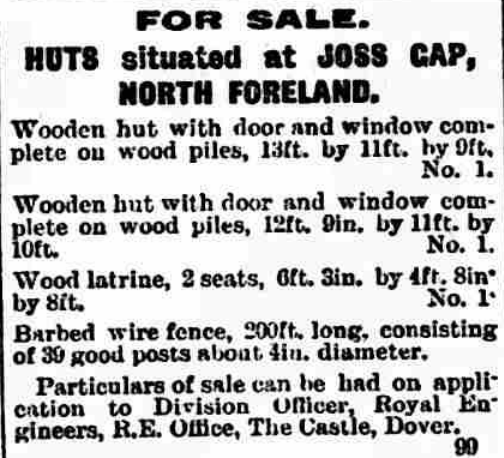

Advert in the 1922 Thanet advertisor, showing the acoustic station assets being sold by the Royal Engineers (British Newspaper Archive)

In search of ever lower frequencies the scale of sound mirrors continued to increase. While plans for a 471ft wide strip mirror at Dover never came to fruition, one spanning 200ft was constructed at Denge (and another was eventually built in Malta). So large that it required a series of independent listening stations and microphones positioned along it, this invention far exceeded the scale of what was undertaken at Joss Bay and arguably the bounds of reason too. Incomplete until 1930, the Denge experiment formed the premise of an expensive plan to position 200ft strip mirrors every 16 miles, all the way from Norfolk to the Dorset coast. It was an untimely proposal given aircraft technology was advancing flight speeds (which reduced the detection times offered by sound mirrors) and, with radio experimentation already delivering encouraging results, a number of scientists were growing concerned about the wisdom of such an investment. Radar research under Watson-Watt, codenamed operation cukoo, had already been gaining confidence in its capacity to supersede Tucker’s work, and in 1936 tests at Orford Ness set out to prove it convincingly before MOD funds were squandered. The consequence was an unequivocal victory, when radio waves showed they could track an aircraft reliably at 80 miles.

The Denge 200ft strip mirror under construction near Dungeness (Scarth 2017, pg. 100)

While it was clear that radar had now thoroughly outmoded acoustic detection, the infrastructure and coastal positioning sound mirrors left behind facilitated the rapid implementation of radar systems during the lead up to the Second World War, and a number of chain home low radar stations were situated on their former sites.Tucker was eventually relieved of his post and faced the final humiliation of being ordered to test the containment potential of sound mirrors on explosive blasts - experiments that would ultimately demolish his Denge creations. Thankfully these never took place, and the monolithic sculptures still survive near Dungeness today, where they serve as monuments to Tucker’s lifework and vision.

For further reading on the history of sound mirrors and acoustic detection please see:

Northall, Lawrence (2020) Kent's Coastal Sound Mirrors, CITiZAN

Scarth, Richard (2017) Echoes From the Sky, Independent Books, Bromley