Changing Minds, Changing Coasts

05/11/2021 | Oliver Hutchinson, Danielle Newman & Lawrence Northall

Update!

The Changing Minds, Changing Coasts project has won a Highly Commended award from the Council for British Archaeology in the category of Archaeological Innovation!

Climate change represents one of the greatest challenges to our species and the future of our planet. Coastal communities will bear the greatest burden of these impacts as changes in weather patterns produce more frequent storms, flooding and erosion. With world leaders debating strategy and mitigation at COP26, it is often difficult to communicate the immediate and local impact of these issues and show how one small change could affect the future of a community.

Through conversations with local volunteers and six years of CITiZAN survey work on the island, we are aware of the degree of coastal change that has happened on Mersea in a relatively short period of time. Projections by Climate Central suggest even greater and more challenging changes ahead. With this in mind, we wondered what climate stories (see Rockman and Maase 2017) we could tell by looking at Mersea Island through the unique lens of local memories. But the COVID-19 pandemic made such a study a difficult prospect.

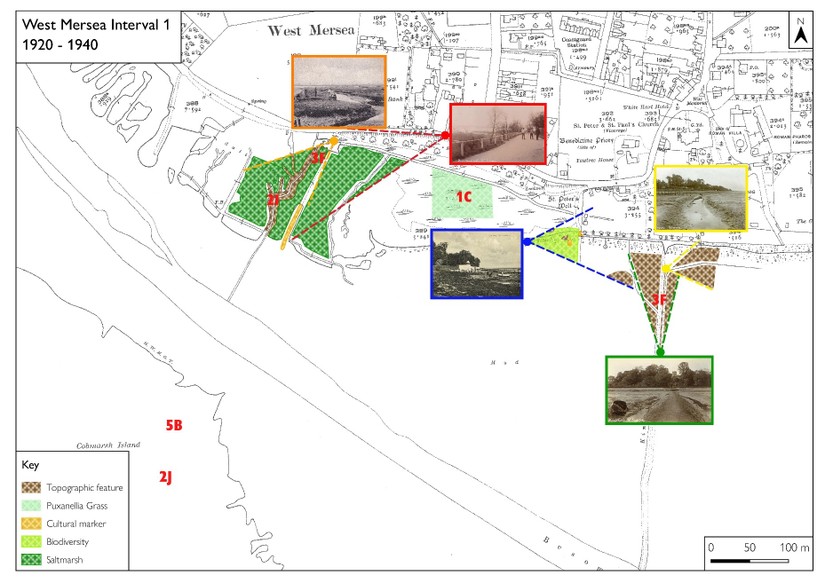

A funding call from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) to develop new ways for the public to participate in scientific research of the natural environment under lockdown conditions provided an opportunity to trial a novel approach to working remotely with our Mersea Island volunteer team. A pilot study, CMCC was developed to establish and map the nature and scale of coastal change on Mersea Island over a 100-year period by co-creating datasets with local volunteers. These datasets included oral history recordings, photographic and postcard archives, and historic maps. Archaeological features provided a proxy baseline for the pace of change on the foreshore. Considering COVID-19 restrictions, the only access the CITiZAN team had to the chosen sites was by proxy, through local volunteers taking contemporary photographs (though we were fortunate to be able to visit at key points during the project).

The sites of Monkey Beach, West Mersea and Cudmore Grove, East Mersea were chosen to represent both ends of the island. By speaking with volunteers, a series of six indicators were developed that represented their experience of coastal change on the island. They were:

1.Presence of archaeological features e.g. structural timber posts, stakes and pottery fragments.

2.Presence and character of saltmarsh, a common feature of the Blackwater estuary which once ringed the island, extending to the modern low water line.

3.Range of Biodiversity, limited for this study to the presence or absence of shellfish, seaweed and seagrasses on the foreshore.

4.Sedimentary makeup of the foreshore e.g. muddy, sandy, shingle, clay.

5.Location of the high and low water lines

6.Cultural use of the foreshore e.g. fishing, winkling, recreation, military use etc.

These indicators were analysed in 20-year intervals for each site to create timelines and maps which could analyse and compare to known environmental events (such as the 1962-1963 Big Freeze winter) and human driven changes (such as the increase in agrichemical use post WWII) that have influenced coastal change on Mersea. By using social media and virtual quizzes, the project was able to engage with locals to gain more insight into specific events and memories our research had identified as being key moments of change.

We’re proud to say that the project has been featured in Current Archaeology 381 (December 2021). Our project report, and interactive StoryMap below, help reveal the story of the relationship between human action and nature on Mersea Island, as told by those most knowledgeable – the local community. They indicate a complex and gradual picture of change between 1920-2020 with erosion increasing exponentially throughout the period. They show that a balanced foreshore environment provided a defence against erosion and that a decline in foreshore biodiversity, combined with the impacts of other factors, events and natural processes accounts for an acceleration in coastal erosion.

But simply writing the reports is not enough. One of the major impacts of this project was empowering this coastal community to connect with and acknowledge the huge changes to their coastline. The datasets serve as both a window on the past that highlights the natural barriers to coastal erosion that our actions so often destroy, and as a proxy for the challenges the community face in the present and the future. Through examining anthropogenically driven climate change over the past 100 years, the project has facilitated local conversations about a global challenge, and placed residents, their experience, knowledge and personal archives at the centre of the debate. We hope that by expanding this model members of the community will become better informed on how and why these changes have occurred and galvanised to act positively to create a more resilient community in the face of further changes.

Therefore, by combining a community’s memories of change with a photographic record spanning 100 years we have created a framework for the community to create its own climate story.

Watch our #ClimateHeritage story on the project above, listen to a podcast on our research on ThePastCast or read the full project report.

With thank all those in Mersea’s community who have contributed their time and wisdom so kindly to CITIZAN and the CMCC project. Special thanks must go to Mark and Jane Dixon, James Pullen, Carol Wyatt, John Pullen-Appleby, Alan Williams, Kevin Bruce, Jack Botham, Ron Green, David Stoker, Dave Conway, Don Rainbird, Brian Jay, Lee Morrison, Daniel French Snr, Daniel ‘Bubby’ French, and David Cooper, Tony Millatt and Joanne Godfrey of Mersea Island Museum