African-Caribbean prisoners of war at Forton Prison 1796-1800

14/10/2020 | Abigail Coppins

In celebration of Black History Month, we have invited a Historian and Archaeologist, Abigail Coppins to share this intriguing story which forms part of her PhD research into African-Caribbean prisoners of war. The PhD is jointly funded by the University of Warwick and English Heritage.

Introduction

The importance and potential of estuaries, shorelines and creeks around Britain’s coastline has long been highlighted by CITiZAN’s projects that record historical and archaeological sites around our shores. Away from the watery edges of these sites, yet still close to their shorelines, there are places with stories to tell of the communities, buildings and people who once lived around their shores. Uncovering these stories can reveal seldom told and surprising histories, which can change what we know about our local area and make us rethink and reassess the past.

Forton Lake and Prison, Gosport

One such place is the area around the tidal creek called Forton Lake in Gosport, Hampshire. It is an area where both the Nautical Archaeological Society and the Maritime Archaeological Trust have already completed surveys of the Lake’s forgotten hulks. CITiZAN have also conducted guided tours of these hulks.

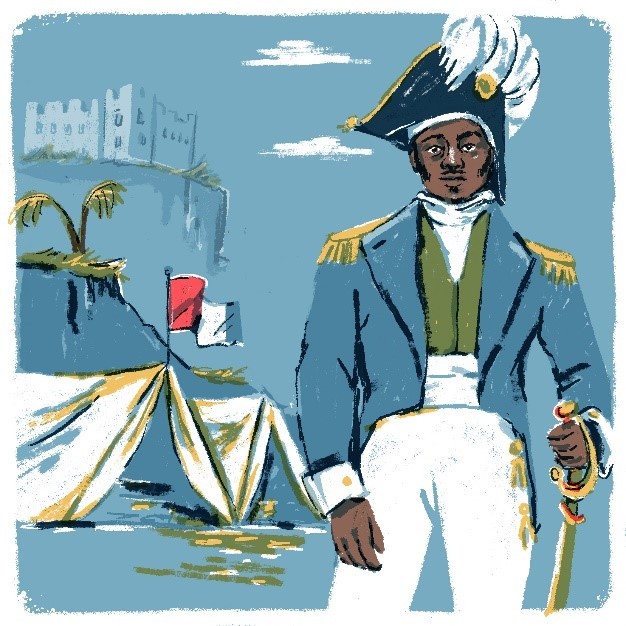

Less well known is that during the 18th century, a military prison stood close to the Lake’s shore which, during the 1790s, held hundreds of French African-Caribbean men, women, and children as prisoners of war. These people had been captured and imprisoned in the war between Britain and France in the southern Caribbean during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (1793-1815).

Their presence inside the prison at Forton provides a tangible link between the area around Forton Lake and the struggle for freedom and emancipation by African-Caribbean people in the 1790s.

Forton prison's African-Caribbean prisoners of war 1796-1800

The numbers of African-Caribbean people held prisoner inside Forton Prison is surprising, at least 600 men (mainly soldiers) and over 100 women, children, and infants. All were from a much larger group of over 2,000 African-Caribbean men, women and children who arrived in the area in October 1796 as prisoners of war. Imprisoned initially at Portchester Castle, the most vulnerable amongst them - the women, children, the sick and wounded - were sent to the prison at Forton due to a lack of space at Portchester.

The numbers arriving are striking: over 2,000 prisoners. This is an exceptionally large group of African-Caribbean people to have had in Hampshire in the 1790s. Estimates suggest that at this time there may have been only around 10,000 Black people, and people from a Mixed ethnic background, in London and perhaps 5,000 in the rest of Britain. To have had women and children amongst them is even more unusual and for Hampshire, this number is unprecedented. The county has always been thought of to have had little Black history.

Click here for more information on Black lives in 18th century Britain and Hampshire.

Who were they and how did they come to be in Hampshire?

Forton’s Caribbean prisoners of war had been captured during fighting between Britain and France on the Caribbean islands of St Lucia and St Vincent. These islands were at the centre of a struggle between Britain and France for control over some of the most valuable islands in the Southern Caribbean, where an enslaved workforce was used to produce valuable commodities, such as sugar, for sale in Europe.

The system of slavery in the Caribbean was challenged when France declared war on Britain in 1793 and then, in 1794, declared slavery abolished on some but not all of the French-owned islands in the Caribbean. Britain, meanwhile, continued the system of slavery in their Caribbean colonies nearby.

As a result, large numbers of people newly freed from enslavement by the French joined locally raised French military units to fight against Britain, and against the system of slavery. In 1796 Britain invaded and took control of French owned St Lucia and St Vincent and began to re-establish slavery on those islands. The mainly African-Caribbean soldiers and their families who were defending the islands surrendered to British forces and were brought to Britain as prisoners of war, where they were imprisoned at Forton and Portchester.

A forgotten history - why does this matter?

Until recently the history of the African-Caribbean prisoners at Forton and Porchester had been overlooked by historians. Now, an exhibition and other projects by English Heritage, the University of Warwick and Elaine Mitchener, have begun to explore their lives further.

For more information follow the links below -

University of Warwick projects at Porchester

Elaine Mitchener's work at Porchester Castle

By uncovering their story, we can get a glimpse into lives that we had known little about. Lives like that of Daniel Chanouette, an ‘Infant of Coulor [colour]’ who was 3 months old when he died inside Forton’s prison in March 1797. The document that records his death gives few details about his brief life besides his name and the date and cause of his death. His parents’ names are not recorded but they were from amongst the African-Caribbean prisoners. Daniel’s presence inside a prison that held prisoners of war in the 18th century is surprising. It can be easy to assume that the prisoners would almost exclusively be adult men and that they will have served in the military. Yet women, children, and civilians, could also find themselves brought to Britain and incarcerated as prisoners of war.

Daniel’s brief life, and the lives of the other African-Caribbean prisoners at Forton and at Portchester Castle points us towards new ways of looking at historical and archaeological sites in Hampshire and elsewhere. People may think they know these places, interpreting them as military sites, spaces were only men were present, or perhaps only people of one race. The history of Forton’s African-Caribbean prisoners shows that this was not always the case.

What happened to Forton's African-Caribbean prisoners?

The African-Caribbean prisoners at Forton and at Portchester were eventually released and sent to France where the men joined French regiments and continued their military service. The women and children followed. Some even made it back to the Caribbean and continued fighting against slavery in places such as Guadeloupe and Saint Domingue (Haiti). Others were recruited into the British Army and the Royal Navy.

Conclusion

I often wonder about young Daniel when I am doing my research. I wonder who his parents were and how they felt when they heard they were to be released from Forton’s prison. Perhaps they were relieved to leave the prison and Britain’s cold climate, yet apprehensive about what the future held. I think that, as they stepped onto the ship that would take them to a new life in France, they were also sad because they could not take their son with them. They would have to leave him behind, buried somewhere at Forton.

The presence of African-Caribbean prisoners at a forgotten prison on the shores of a small tidal lake in Hampshire may come as a surprise. Yet their presence serves as a reminder not to make assumptions about historic and archaeological sites. Their histories may well be more diverse, exciting and enriching that we imagine.

Further information

An English Heritage ‘Speaking with Shadows’ podcast talks about the lives of the African-Caribbean prisoners including bonus episode featuring Elaine Mitchener’s sound installation | Les Murs Sont Témoins | These Walls Bear Witness |