Alnmouth: "A Nice Clean Place"

09/10/2020 | Angus Stephenson

This blog is about Alnmouth, a small former fishing village on the Northumberland coast, about halfway between Newcastle and Berwick, and about 30 miles from each. One of the main reasons it may be of interest to the CITiZAN readership is what happened there on Christmas Day 1806 but first some topographical and historical context.

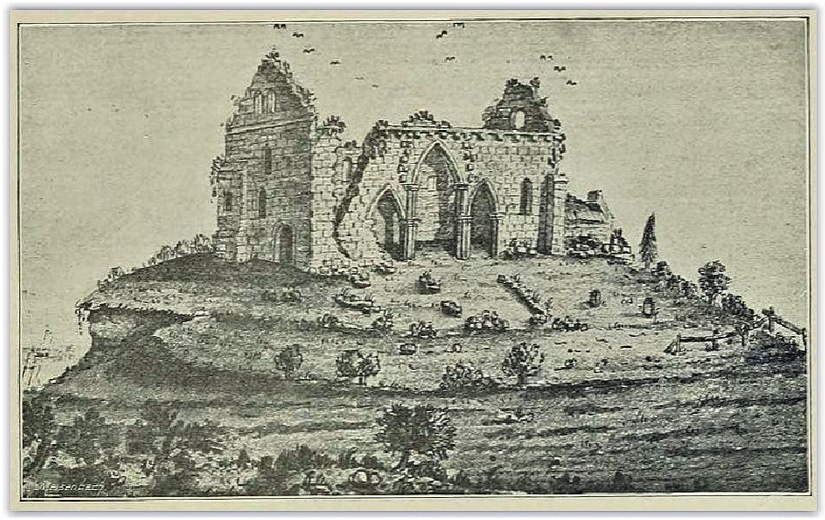

The village takes its name from the river Aln(e) which completes its sluggish and meandering route down to the North Sea there. It is almost certainly the place described by the Venerable Bede as Adtwyfyrdi (“At two fords”) on the river Alne, where a synod, a high-level religious meeting, was held in 684 to elect new bishops for the dioceses of Hexham and Lindisfarne. A synod implies a recognizable and respected Christian establishment and it has long been held that there was an Anglo-Saxon church on Church Hill, Alnmouth, before the well-attested medieval version, although physical remains of it have never been found. This view was backed up by the discovery of parts of a later Anglo-Saxon-style cross there in 1789.

The two fords across the River Aln were ancient and long-lasting, and can be seen on many historic maps, one near the site of the 19th century bridge which connects the West side of the village to Lesbury and Alnmouth Railway station, and the other running South-West across the mud-flats to the West of Church Hill. As an illustration of how strong the tides can be, here is a picture of part of the stone revetment wall at the North end of Church Hill, brought down by storm surges in August 2020.

The development of the medieval town dates from the 12th century when William de Vesci was granted permission to start a new town on an area of land taken out of Lesbury Common and his successors were granted the rights to hold a fish-market there in 1207/8. The town had a typically medieval layout with burgage plots extending back from both sides of the main street, with the Medieval version of the church, then known as St Waleric’s Chapel, standing on a sandstone headland to the South, connected to the main part of the town by a substantial sand bar. The river looped round the South end of Church Hill, then up its East side to the sea. This meant that any ships using the harbour could moor in an area protected from the North Sea on the West side of Church Hill, where it is possible that mooring posts and jetties of that date survive below the mud.

The town was never particularly prosperous in the Medieval period. One of the main problems was that it was within striking distance of the Scottish border and raiders swept back and forth across the no-man’s land in this part of the country for the whole period until the union of the crowns in 1603. In the late 16th century Alnmouth was described as “depeopled” and in 1614 as “in great ruin and decay”. Things improved gradually in the 17th century and by the 18th century the town could be described as prosperous, trading extensively in grain exports, with several granaries built around the town and harbour. The church, however, had fallen into disrepair by this time and sat on the crumbling headland as a substantial picturesque ruin, gradually falling into the sea by stages.

Although the port and its associated industries were doing well in the 18th century, a new problem arose from the frequent outbreaks of hostilities between Britain and continental Europe, particularly France, in the shape of privateers, pirates, who regularly made a nuisance of themselves around the coasts of England. Alnmouth had a brush with one of the most notorious of these, John Paul Jones, in 1779.

John Paul Jones is sometimes held up as a hero of the American War of Independence but at this distance in time he is not an easy man to admire. He was a Scottish seaman, who killed one of his crew in a dispute about wages and rather than face trial in Britain, he jumped ship in the Caribbean and stayed in America, where he had immigrant relatives. He offered his services to the nascent American revolutionary navy and was sent to France, where the naval authorities were only too happy to help him cause trouble for the British, which he did with crews comprised mostly of renegades from Britain with French officers and a few Americans thrown in. He repeatedly complained about them as, for example, when during an attack on Whitehaven in Cumbria some of them stayed in the pub too long, instead of burning the place down as they were supposed to do.

W.W.Tomlinson takes up the Alnmouth story in his Comprehensive Guide to Northumberland of 1888: “(In September) 1779, Paul Jones, who had been cruising about the coast of Northumberland the whole day, appeared off Alnmouth at six o’clock, and at eight o’clock took a brig. He then continued his course south, after firing a cannon shot at the old church. The ball missed but grazing the surface of a small field east of Wooden Hall, struck the ground and rebounding three times, rent the east end of the farmstead from bottom to top. It weighs 68 pounds and is in the possession of Roger Buston Esq, of Buston (Hall), a country house about a mile and a half from Alnmouth.” After this spectacularly inept bit of target practice, the squadron sailed South to fight in the Battle of Flamborough Head off the coast of Yorkshire, and John Paul Jones went on to become the bass-player in Led Zeppelin.

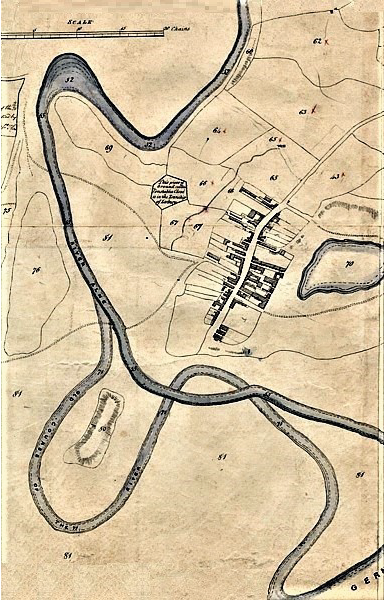

On Christmas Day 1806, the topography of Alnmouth was changed irrevocably. The sea crashed through the sandbar connecting the town to Church Hill, and the last remnants of the church/chapel were blown down into the sea. Slowly the loop of the river round Church Hill silted up and that part of the harbour disappeared. It has been argued that the town was already in decline when this happened but a strange prolonged period of lethargy seems to have taken over the place subsequently, which lasted for some 50 years. The tithe map of 1843 shows the old and new courses of the river, before and after 1806, as it heads for the German Ocean at the bottom right of the map.

The picture below shows Church Hill from the West and the mud flats in the foreground are the site of the medieval harbour. The new course of the river cut off Church Hill from the main part of the town, shown by the red roofs of the houses on the left. At high tide nowadays this foreground area is under water.

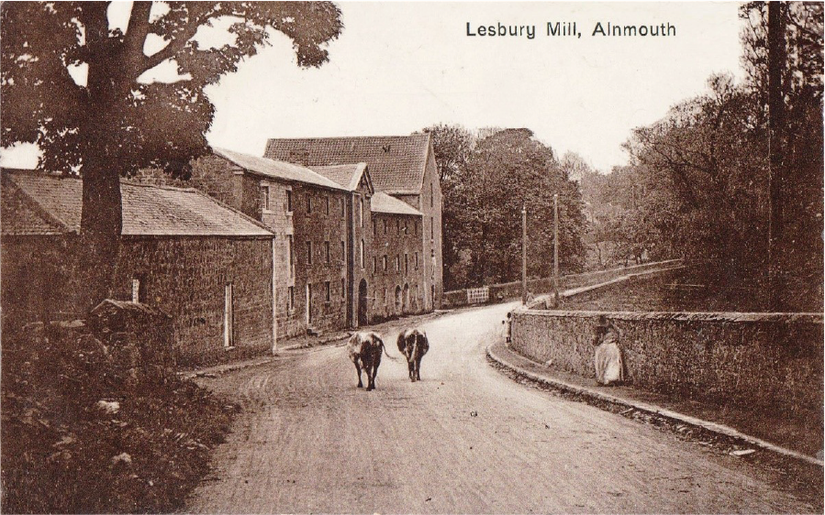

In the early 19th century, the community of Alnmouth seems to have floundered. There was no church in the village and maintenance of the old graveyard to the South of the old church on Church Hill seems to have been neglected. Nearby Lesbury took the lead on matters spiritual. Volumes of trade dropped off for Alnmouth harbour and the activity of its fishing fleet dwindled to very little. The railway arrived at Alnmouth station in 1847 and from then on that was the way in which grain was shifted about the country, rather than by sea, but the railway also allowed Alnmouth to reinvent itself. The town changed its identity from being an industrial town with docks, shipyards and warehouses, although they all staggered on until the end of the century, to become a rather genteel Victorian holiday resort, with the granaries converted into guest houses and an early 9-hole golf course. Here is a postcard from Auntie Margaret to her niece Cathy in London in c 1910: “I do wish you and Sophy could have your spades and dig in these sands. It is such a nice, clean place.”

The fishermen became quaint anachronisms, suitable subjects for the fashionable pseudo-ethnographic postcards of the day, although small-scale sea-fishing carries on to this day.

In the mid-19th century, Alnmouth experienced a wave of renewed religious energy. The Duke of Northumberland seems to have triggered it in 1859 by converting one of his old granaries in the town into a temporary chapel and shortly afterwards a public subscription paid for a new oratory or mortuary chapel to be built on Church Hill. The graveyard land there was enclosed at the Duke’s instigation and a cottage for a sexton was built at the same time. The town’s ferry took people across the estuary to Church Hill and the graveyard may have been brought back into service, but there is a lot of uncertainty about all of this, as most funerals for Alnmouth folk still took place in Lesbury. There are said to be 19th century gravestones on the hill but they are difficult to spot because it is so overgrown. None of this reinstatement lasted long, however, as a new church on the North side of the town was built in the 1870s with an attached churchyard and that was where the congregation went after that.

So was this nice clean place as idyllic and trouble-free as it seems, with the local people pursuing the silent tenor of their doom through the cool sequestered vale of life? Possibly not all of the time. Here is a postcard from Aunt Z to her niece Miss E. Smith in Newcastle in 1919: “Dear E, White is alright. A bit slackness on his part. I act as P.O. every week for chocolates. It comes in very nice. I refuse nothing. There is an old man here offered me a situation to be his housekeeper, and how I laughed when he asked me, the frivolous old devil! Love from your Aunt Z.” Dark currents, indeed!

To the South-West of the mudflats and salt marshes that have formed as a result of the river changing course as it previously looped round the South end of Church Hill is a large, derelict agricultural building. It was given Grade II listing in 1988, when it was described as being of 18th century date, although the cartographic evidence suggests that it was actually built in the second half of the 19th century. The building is known locally as the Guano Shed and would definitely not have been nice and clean.

The guano trade was a somewhat bizarre industry, which flourished between 1840, although its first stirrings were a little before that, and 1880. Guano is a Peruvian word for bird droppings. Where these have accrued and become sufficiently compressed they can be mined and used as fertilizer because of their high content of nitrogen and other chemicals; guano could also be used for making explosives because of the high ammonium nitrate component of some types. From the mid-19th century, imported labour was used to dig the thick deposits of seabird guano on islands off the Peruvian coast in predictably disgusting and exploitative conditions. From there vast quantities of it were taken by ship round the Horn and up the Atlantic to Britain through the ports of London, Bristol and Liverpool in particular, where it was distributed by boat and train in smaller quantities to end users. Alnmouth received guano from London and it was supposedly stored in this building. It is usually assumed that the guano shed at Alnmouth was situated here because of the stench, although the storage of huge amounts of materials containing ammonium nitrates near a town might not be advisable for other reasons, as the people of Beirut would be keen to point out. The guano trade lasted until about 1880, after which European research found ways of getting the right chemicals for fertilizers and explosives that were easier than shipping boatloads of bird manure halfway round the world.

After the end of the guano trade the shed appears to have been used for other more routine agricultural purposes. At some point slots were cut into all of its walls and it is assumed that this would have been for guns during the Second World War to resist the threatened invasion. Today the building is in a very sorry state. It has lost its roof since the 1988 listing and parts of the masonry north gable and other walls have collapsed. Unless some remedial conservation is carried out, that will be the fate of the rest of the building. It would be a shame to lose it, as it can reasonably be described as a unique monument, and could serve as a memorial to a vanished industry.

The last picture shows Church Hill looking South at high tide, with sea water showing the position of the former Medieval harbour on the right. The cross is intended to indicate the position of the lost church, whilst the concrete block behind it was the base for a World War II pill-box. The hill is visibly eroding and as it does so it is likely to reveal more details of its past before it slips into the sea.

References:

This article is largely based on four reports, the first two of which are available online. I am very grateful to all of the authors for sending me digital copies of them:

Caroline Hardie, Rhona Finlayson, Alan Williams, Karen Dernham (2009): Alnmouth Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey.

Caroline Hardie, Penny Middleton (2009): Historic Environment Survey for National Trust Properties on the Northumberland Coast: Buston Links, Alnmouth.

Kristian Strutt (1998): Signs of Ritual and Industry: An Archaeological Survey of Alnmouth.

Alan Williams (2003): The Guano Shed, High Buston, District of Alnwick: Archaeological Assessment.