Hallsands: Fishing Tales And The Village That 'Went To The Sea'.

11/11/2020 | D Wootton

Have you heard of the famous ‘lost village’ of Hallsands on the South Devon Coast? Situated within the Start Bay area, it was a small fishing village with a strong local community. It was lost to the sea in 1917, following a series of devastating winter storms and controversial gravel dredging.

Recently, I was fortunate enough to meet Roger, who is a descendant of a Hallsands family, through his grandparents George and Blanche Steer. Roger related many tales of what life was like to grow up in a fishing community and was happy to agree for me to interview him. The story of Hallsands is complex; each family had their own experience and memories. Here I give a short and simplified account of the village, with the aim of providing background and context as an introduction to Roger’s fantastic interview, which will appear shortly as part of a forthcoming Low Tide Trail.

The Village of Hallsands is thought to have developed around the 1600- 1700’s. It’s unlikely to have existed before this time, as Devon communities tended to build settlements away from the coast so they weren’t visible to passing pirates. The earliest reference appears to be in 1611, where a tenement is referred to as ‘the great Sellar, Hallsande Chappell’.

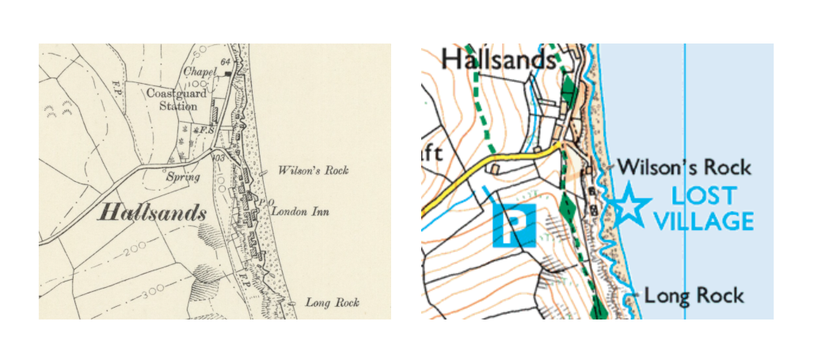

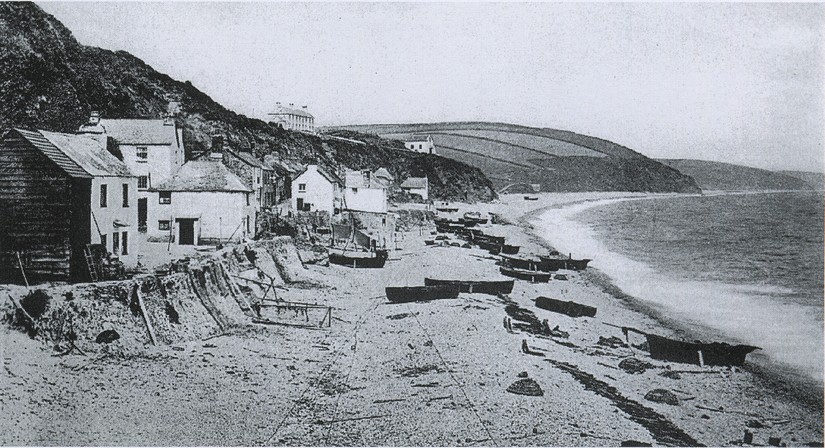

Over time, the settlement grew into a close-knit fishing community and by 1891, there were 37 houses at Hallsands and 159 people were living there. Old photographs show families gathered together along the sea wall making crab pots, another depicts a busy scene with men and women gathered on the beach pulling in a large fishing net known as a ‘seine net’. The Ordnance Survey map of 1907 shows Hallsands having one main street running parallel to the beach, with houses built either side of it; there’s a chapel; a post office; and a pub called the ‘London Inn’. Today, the modern Ordnance Survey map of the area reveals a stark contrast: it is marked as a ‘Lost Village’; the road, houses, post office, and the pub no longer exist. But what happened to the village?

It’s a long and complex story, and research still continues, but it’s likely that the destruction of Hallsands village was a ‘double-whammy’ of human intervention and the forces of nature. According to recent research published in 2017, it appears that the dredging coincided with the beginning of a phase of North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) from 1900 to 1930. This extended phase of NAO meant there were less easterly waves and more westerly directed storm waves, causing the sediment to shift around in Start Bay.

The beaches around southern Start Bay would have narrowed, and the northern ones would have widened. The narrowing of the beach at Hallsands meant that it was unprotected from storm waves. However, many claim the dredging of this protective gravel barrier contributed to the narrowing of the beach which ultimately led to the destruction of the village.

The village was set on a raised platform of metamorphic rock known as Start Mica Schist. On one side of this rock platform was the shingle beach, and behind the platform were cliffs. The rock had many deep holes or ravines, which overtime had been filled up with sand and gravel. The platform was raised above sea level and the shingle beach protected the village from the tides. It was on this rock platform that the houses were built; some of these houses were built on top of the in-filled ravines, with some of the houses backing directly onto the cliffs.

Our story now travels around 30 miles westwards along the coast to Plymouth. Here, in 1894, plans were made to extend Devonport Dockyard. To complete this extension, vast quantities of sand and gravel would be needed to make concrete. Sir John Jackson, a local contractor and civil engineer, who had previously worked on projects such as the Manchester Ship Canal, began to look for a suitable place to conduct the huge undertaking of gravel extraction.

Jackson’s company originally began offshore dredging further east along the Devon coastline at Exmouth, but this had to be stopped due to concerns raised by the landowner that the dredging would form a new channel which would damage the town. Jackson had to find elsewhere. He was granted a license by the Board of Trade to dredge the shingle in Start Bay around the villages of Hallsands and Beesands. According to local accounts, villagers knew nothing of it until one morning in April 1897, a dredger appeared in the bay and the dredging began- it’s been estimated that around 1600 tonnes of shingle a day were being dredged- and this continued for the next five years until 1902.

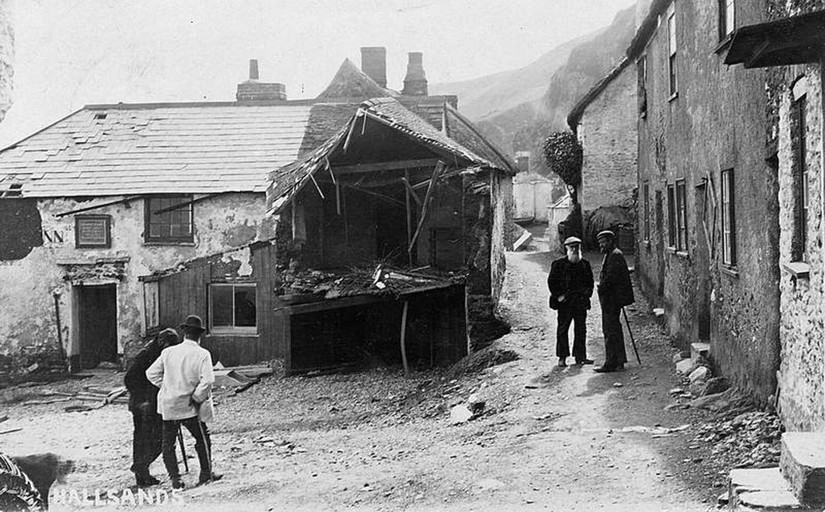

Many of the villagers were immediately concerned that the dredgers would frighten away the shoals of fish upon which the community’s livelihood depended. Various battles and pleas for help ensued. Soon villagers started to notice cracks in the walls of houses and during storms in 1900 and 1901, the old sea walls, built 30 years earlier, were underrnined and the sand and gravel started to erode from the ravines. The houses which had been built on the sand and gravel had no real foundations and several buildings collapsed and many buildings, including the London Inn were severely damaged.

Over the years, the community petitioned for help. A local MP, Mr Mildmay, made many visits to the village and was in support of the community; he raised the matter in parliament and for many years helped to campaign on behalf of the villagers. Other supporters included the engineer Mr Hansford Worth, who argued that the shingle that was being dredged would not be replaced naturally; and Mr Henry Ford of the Devon Sea Fisheries Protection Committee. An appeal was launched by the Western Morning News and new cottages were built higher up the cliff to provide for families who had lost their homes in the storms. They were named Mildmay Cotttages, after the local MP.

Eventually, Sir John Jackson’s licence to dredge was revoked on 8th January 1902 and the dredging stopped. By this time, an estimated 650,000 tonnes of shingle had been removed and the beach level had fallen by an estimated 3 metres. Coastal defences were constructed behind the narrowed beach, which provided the villagers with some protection for several years.

However, on 26th January 1917, a severe storm was approaching. Villagers dragged their fishing boats up to the village street and battened everything down for protection. Children were evacuated to the relative safety of nearby Mildmay cottages. There was a particularly high tide expected that evening, due to spring tides, and there was already a howling northeasterly gale.

There was nothing to do now but wait. Around 8pm, in the darkness, the high tide hit. The waves were reported to be 12 metres tall- so high that they went over the sea walls and pummelled the roofs of the houses from above. Sea water cascaded down chimneys and flooded the floors as the howling wind battered the buildings from outside. It must have been terrifying. During a lull at low tide, the villagers salvaged what they could and escaped to safety. Amazingly, all 79 of them survived. The storm continued to rage and when the next high tide came on the 28th January, the waves broke through the sea walls and caused dreadful damage; 29 houses were destroyed; leaving only two houses standing, and the village was lost forever. The local Gazette led with the headline ‘The beach went to Devonport and the village went to the sea’.

The story of the lost village of Hallsands is a tragic one, but it doesn’t end here. Many villagers moved less than half a mile along the coastline to North Hallsands (known locally as Greenstraight), where they continued to fish for a living. Today, descendants from Hallsands and Beesands fishing families continue to fish and meet at the Cricket Inn to recount tales of past times. The stories contain a mine of information about the coast line, fishing stories, and days gone by. I hope you will enjoy Roger’s tales- he certainly knows how to spin a good yarn. Best of all, he’s currently writing a book about his family and the villages of Hallsands and Beesands, which he plans to bring out next year.

In the meantime, I hope you’ll enjoy Roger’s stories which range from how the Cricket Inn at Beesands got its name, how locals navigated a notoriously dangerous coastline before GPS, and a humorous tale of how the villagers used to dupe the water bailiff when salmon fishing wasn’t allowed on Sundays…obviously not to be advocated.. but nonetheless a great fishing tale…enjoy!

With sincere thanks to Roger and his wife Carol, and other members of the local community for their help and support with writing this article.