Dunkirk 'Little Ships' & the Thames Barge

26/05/2020 | Gustav Milne

DUNKIRK’S ‘LITTLE SHIPS’

When discussing the role of shipping in WW2, images of battleships and U-boats spring readily to mind. But it’s worth remembering that for all on the east and south coast, all the vessels boats, barges, coasters, trawlers, tugs, pleasure steamers, merchantmen – had key roles to play, in just the same way that London’s Blitzed civilian population suddenly found themselves in the front line.

In this article we focus on the fate of Thames Sailing Barges (TSB), once such a common site all along the east coast of England. Alas, too many of these once proud vessel lie forgotten and abandoned in creeks and backwaters. CITiZAN is eager to promote the survey of these important vessels, given the great contribution they made to our coastal economy and maritime history.

Dunkirk ‘Little Ships’ from the Thames under tow. Passagemaker.com/trawler-news/dunkirklittle ships

OPERATION DYNAMO

But first we look at one of the major contributions that civilian craft made to the War Effort, focussing on the Dunkirk evacuation of 1940. In May of that year, the German army had invaded France, and the Allied forces were all too rapidly overwhelmed. The British Expeditionary Force found itself trapped on the exposed coast near Dunkirk, with the German Army encircling them on land and the Luftwaffe attacking them from the air. An emergency evacuation was hurriedly planned (code-named Operation Dynamo). This involved privately-owned ships, boats and barges from the coasts and rivers of southern England being requisitioned or volunteered for service to work alongside the Royal Navy, in the seemingly impossible task of rescuing the Allied armies at the eleventh hour. The beaches of Dunkirk were wide and flat, and so large vessels could not get close enough to the shore to lift the troops out. What was desperately required were many smaller, shallow-draft vessels that could sail right up to the troops wading out into the sea, pick them up and transfer them to the larger vessels moored offshore in the deeper water.

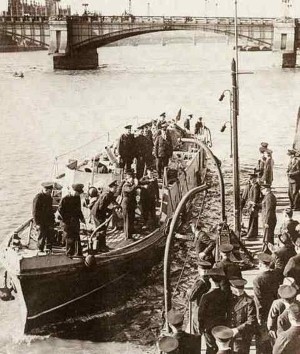

Massey Shaw fireboat return to London, June 1940. nationahistoricships.org.uk

The story of what happened next is well-known, a tale of near tragedy turned into a near triumph. This was thanks to the extraordinary courage of the crews that manned the armada of 311 ‘Little Ships’ (including the fireboat Massey Shaw (shown left), 113 trawlers and 34 tugboats. But the entire operation was conducted under ferocious fire from the Luftwaffe, who made no distinction between soldiers or civilians, between Naval vessels or fishing boats. Somehow, from 26th May to the 4th June 1940, a staggering total of 338,266 soldiers were taken off the beach often in unarmed boats from an ad hoc fleet pulled together from ports and rivers on the east and south coast.

TSB Pudge at Maldon (CITiZAN)

THAMES SAILING BARGES

The Thames sailing barge (TSB) with its readily identifiable sprit-sail rig was a great work horse of Thames-Medway and East coast ports in the pre-war days. It could carry a sizeable cargo, only needed a very small crew, and could make good petrol-free speed under sail. It has a broad flat bottom, and is thus well suited to working off wide shallow beaches, such as those at Dunkirk, where deep-draught shipping could simply not operate. It is recorded that sixteen Thames Sailing Barges set out to do their bit in the summer of 1940.

The exploits of the craft and their crews have been recorded in, for example, Frank Carr’s ‘Sailing Barges’ (1989: pp 357-374). But nine were lost on active service, a heavy price. The names of these humble but heroic coastal craft deserve to be remembered alongside those of mighty battleships: the lost barges were the Aidie, Barbara Jean, Duchess, Doris, Ethel Everard, Lady Roseberry, Lark, Valonia and Royalty.

Abandoned hulk of TSB Ena in 2019 (Adam & Robert Kerry)

But what of those that did make it home? Over thirty years ago, David and Elizabeth Woods recorded the location of the survivors in 1987, in their catalogue, ‘Last Berth of the Sailor Man’, the term often used for those barges. This listing is updated here. Pudge is still active in Maldon and Greta in Whitsable while Glenway and Tollesbury are under restoration. Thyra has been broken up, as has H.A.C and Beatrice Maud.

To end this section, we retell the story of Ena, based on the account from Julian Wilson. Ena set sail for Dunkirk, making the 100-mile journey, in spite of air attacks and the constant threat of mines. After heroic work on the beaches, but with the German army was closing in. Alfred Page, Ena’s skipper, was ordered to abandon his barge alongside another sailing barge, the H.A.C. The crewsmade good their escape back to England on a minesweeper.

No sooner had they left, than thirty men of the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment arrived on La Panne beach. They had been fighting a desperate rearguard action to keep the Germans at bay for as long as they could. Now, with the evacuation virtually over, they could not believe their luck when they saw two barges sitting there, in seaworthy condition.They took possession of H.A.C., while Colonel McKay with men of the 19th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery boarded the Ena. Meanwhile, Captain Atley of the East Yorkshire Regiment, was on the mole at Dunkirk and together with one of his men, quickly made a raft. Using shovels, they rowed out to Ena. and helped 36 other men on board including three wounded. By 8am both barges were under way. In spite of enemy bombardment and machine-gun fire they raced across the Channel under sail, even though there were no naval personnel on board. Eventually, the Ena made it to Margate.

But now, eighty years later, Ena lies abandoned and derelict near Hoo on the River Medway, a sad end to an eventful life. Unlike her sister vessels, Greta and Tollesbury, she is not included in our national Historic Ships List. At the very least, she should be fully surveyed and her subsequent fate monitored, out of respect for the lives she saved 80 years ago.