Writing on the wall: memories, wishes and feelings caught in time, in Kent

20/03/2020 | Tijana Cvetkovic

On a cold November morning I arrived in Sandwich and, after meeting Lara Band, Project Officer and lead archaeologist for CITiZAN’s East Kent Coast Discovery Programme, we started heading along the River Stour to visit a prison. The prison or the Detention Centre was part of a secret harbour, Richborough Port, a harbour built during the First World War with the purpose of supplying troops fighting on the front. The prison itself was made for British soldiers, stationed at the harbour, who had broken rules.

After the war the prison was in agricultural use for more than fifty years and then abandoned and left in oblivion together with the events that happened there and the memory of people who were once forced to stay at that place. Our excitement about the place kept growing while we were there. We were struck by still visible graffiti, left on cell walls by occupants, these sketches now accompanied by artwork of later periods. One of them was just a house, though an unusual one. We took photographs of as much graffiti as we could and went home thinking on the place that was obviously as cold at that time of a year during the war as it was that day when we visited it.

The graffiti of the house had a seemingly illegible text under it but we concluded it was not written in English and hoped to have German words in front of us. And then, during the evening, I created a black and white version of the same photograph which revealed the word ‘Amtshaus’. My excitement about having German writing here was enormous. In German the word describes a state administration facility, an office building responsible for tasks of the public administration, also being the historical name for a building, retained after the change in function.

But my excitement grew, during same evening while searching the internet for existing examples, I saw for the first time Knochenhauer Amtshaus in Hildesheim, in the federal state of Lower Saxony, in Germany. Similarities in the number of floors, the jettying and also in the gable end with what may be the three little pointed windows, the similar look of the main door of the building, part of another building to the left and one more building on the right separated and at an angle, strengthened the belief that I had found the same place.

If it is the same building, the graffiti maker was a German person. Was the building in his hometown or is it a place that he had visited once or many times? Did he draw from memory, a postcard or a photograph? What were his memories related to the place and, above all, how did he feel? Is it that a great desire to be home, nostalgia, resides quietly in our heart when we are willingly far from our hometown but gets greater in proportion when we are forced to be far from it? Or is something else? The sketch is important for us because it changes the history of the place, proving that not only British soldiers were held there but also German prisoners of the war.

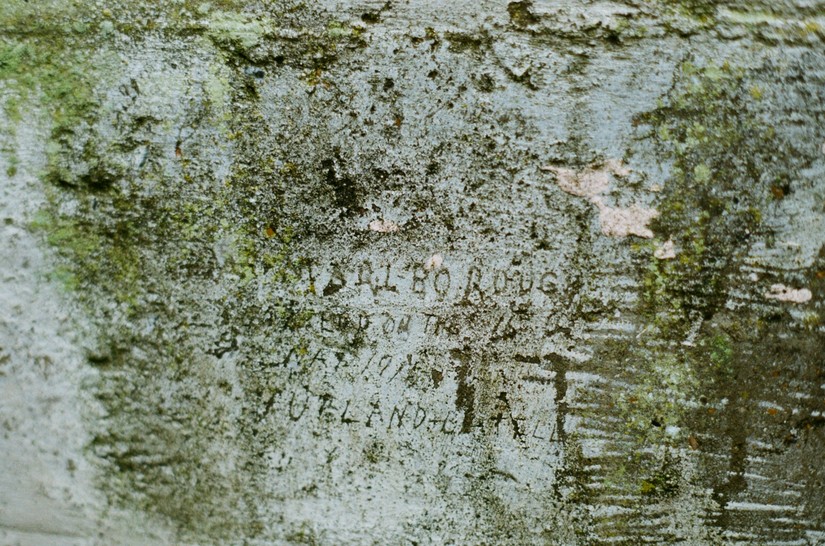

Among other graffiti there is scratched the name of HMS Marlborough and the Jutland ‘batell’ - we dearly embraced the mistakes in spelling the word, possibly made by someone who served on the ship and took part in this naval battle in 1916. My favourite graffiti is a sketch of a woman’s leg in a stocking, made in a truly artistic manner.

Intimate stories, memories, wishes and feelings reside in the graffiti. These stories stay hidden from us. But they were vivid to someone and for that reason these sketches, proof of the inmates existence, are dear to us. We find them precious, we want to know these stories and understand who made them.

And for that reason, our research continues.

If you enjoyed this piece take a look at our previous blog by Andy Sherman, Liverpool Bay Discovery Programme Project Officer on Food culture and the intangible heritage of the North