Seaham: On Chemical Beach

01/07/2020 | Angus Stephenson

Seaham: On Chemical Beach

This is a second blog about Seaham, a small town on the Durham coast, with a diverse and intense industrial past. The first blog, Seaham: “Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know”, outlined its general history and focussed on the Blast Beach. This blog concentrates on the Chemical Beach, immediately to the North, nearer to the town centre, but with more difficult access down to it.

From the mid-19th century onwards Seaham’s heavy industries were served by steam engines using an elaborate and complicated series of railway lines and sidings in the town. Most of these engines had names, such as Mars, Juno and Neptune. The first picture is a view looking South from the cab of one of these engines, called Dick, in July 1955. The Chemical Beach is on the left of the chimney stack, at the bottom of the Magnesian limestone cliffs. In the middle of the beach is the Liddle Stack rock, significantly more eroded in later pictures (e.g. Image 2), and the derelict remains of a former low-level railway line leading towards it. The headland behind is called Nose’s Point and there are coal wagons on it against the skyline, where they used to tip coal waste directly into the sea. To the right of the chimney are the buildings and headgear of Dawdon Colliery, one of the town’s three coal mines, and strings of chaldron wagons for coal transport. Vast quantities of coal were exported from Seaham Harbour by sea in the 19th and 20th centuries. Dick was built in 1895 and retired from service in 1963.

The first docks of Seaham Harbour were built and opened in the 1830s and were originally designed for coal export. Nose’s Point was the site of the Watsontown Iron Works and blast furnaces, which started operating in c. 1855 and lasted until 1888. Their waste was also tipped directly over the cliffs into the sea, so that the beach beyond the Point is known as the Blast Beach. The land for the chemical works of the Watson, Kipling and Petrie chemical company, just to the North, was bought in 1863 and they began trading in 1865, dealing mostly in soda crystals and magnesia. The operation was never a big success and the company was making a loss by 1877 and was finally closed in 1884. The piecemeal demolition of the buildings began in 1900 for the development of Dawdon Colliery, which was in production until 1991. A new coal washing plant was built for the mine in the 1960s and the tunnel for its waste water disposal can still be seen drilled through the cliffs of the Chemical Beach. This is the name which has stuck even though the chemical works was relatively short lived.

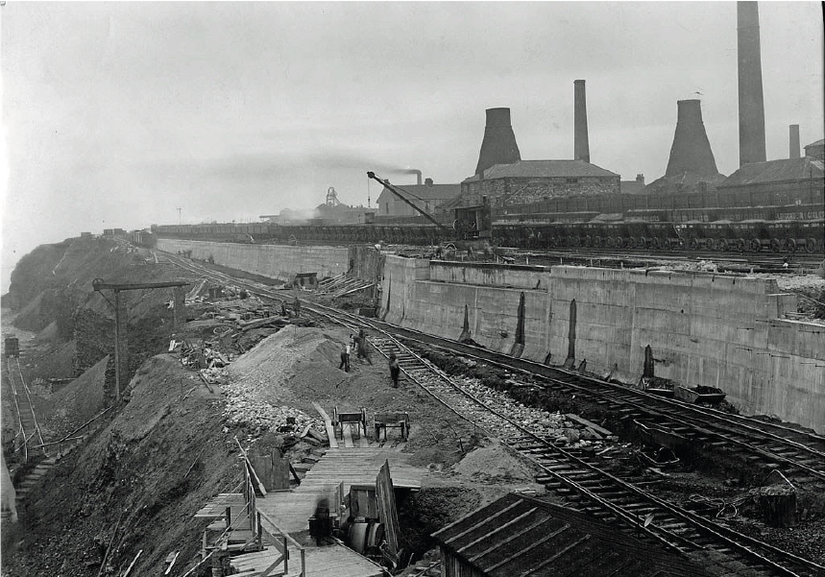

Enormous coal staiths were built beside the harbour so that coal for transport could by dropped directly into the holds of waiting ships. These were timber structures which carried the chaldron wagons at cliff-top level and had huge crane systems for lowering them down to the ships. This inevitably led to some spillage and low level lines were built at the bottom of the cliffs, so that this could be cleaned up and collected. The picture below shows extension work at the docks in 1925, with railway lines visible at both levels and vast numbers of chaldron wagons in service. The cones and chimneys are for the former glassworks, awaiting demolition at this date, and the headgear for Dawdon Colliery can be seen in the background.

The inclines between the two levels of the railway lines presented a formidable challenge to the steam engines and their crews, and accidents and injuries were not uncommon. The best known steam engine used for shunting chaldron wagons is probably the Lewin Number 18, built in 1877, decommissioned in the 1970s and acquired soon afterwards by Beamish Museum, where it can be seen nowadays in its restored state. Seaham was famous for its chaldron wagons, which were typically bottom-emptying four-ton containers for use on the staiths and for spillage collection, examples of which can also be seen at Beamish. Such wagons continued in use at Seaham until the 1970s.

The chaldron wagons are all gone now but a relic of them can be seen at low tide on the Chemical Beach. Locally it is just known as The Wheels.

Seaham Harbour entertained a vast amount of boat traffic and unsurprisingly a very large number of shipwrecks have been recorded in the area, although many of them are not particularly well-located. In 1824 the Royal National Lifeboat Institution was founded with the aim of organising a national lifeboat service and in 1870 they supported a proposal for a lifeboat station to be built beside the harbour, which was done on a site provided by the local industrialist and magnate, the Marquis of Londonderry. Much of the funding for the first actual boat to be housed in the station was raised by a family of sisters selling needlework and other items from their home in Harrogate, and this boat was duly called “The Sisters Carter of Harrogate”. Several other boats were subsequently based there. The station was closed in 1979 but still stands and was renovated in 2012 as the East Durham Heritage and Lifeboat Centre, the building with a grey roof in the centre of the picture below.

The most famous Seaham lifeboat is the George Elmy, paid for by a London spinster named Elizabeth Elmy and named after her brother. This boat was called out 26 times and carried out several rescues between 1950 and 1962. On an afternoon in November 1962, the George Elmy was called out to assist a fishing boat that had got into trouble in stormy seas and its crew of five put out to sea to rescue the five people on the fishing boat. On the way back the lifeboat was hit by a ferocious squall just outside the harbour and capsized. Of the ten people on board only one, a member of the fishing boat crew, survived by clinging on to the upturned boat as it was washed up on the Chemical Beach.

The derelict timber structure in the images above are still to be found on the beach, and can be seen in some of the previous photos in this article, although it is visibly being eroded. The details of its original usage are uncertain.

The lifeboat was badly damaged but was put back into shape by the RNLI and used as a relief vessel before being transferred to Poole Harbour on the South coast, where it served as a lifeboat until 1972. After that it spent several years as a fishing boat in relative obscurity before being spotted by a member of the East Durham Heritage Group up for sale on ebay in Holyhead in Wales in 2009. The boat was duly purchased by the group and brought back to Seaham, before spending several months undergoing restoration at a boathouse on Tyneside. In June 2013 the George Elmy was sailed down the coast back to its current home in the restored lifeboat station at Seaham Harbour, where it can normally be visited (This article is being written in early 2020 during the coronavirus lockdown).

Seaham's Most Famous Son

No visit to Seaham would be complete without a mention of its most famous son, Tommy, the sculpture of a Great War soldier, by local artist, Ray Lonsdale, standing near Seaham’s war memorial, where he has been since 2014, the centenary of the outbreak of that war.

An article in the Sunderland Echo, dated 11th December 1914 reads: “Recruiting at the drill Hall, Seaham Harbour, for Lord Kitchener’s Army, is still proceeding and over 600 recruits have been sent from the town by Mr H. Webb, recruiting officer for the district, since August 12th, when the office was opened. Previous to this upwards of 60 men were sent to Sunderland. Considering that apart from this, the Seaham District has a Territorial Brigade of artillery embodied and a reserve brigade in training, the enrolment of the 600 men is considered to be very satisfactory.” The town was shelled from the sea by a German u-boat in 1916.

Seaham is a long way from London and could be described as being a bit off the beaten track but every now and then its influence can be found in unlikely places. Here is a mural on a South-East London housing estate wall. I wonder where the schoolkids got the idea for that design from?

Further Reading:

https://seahampast.co.uk/ (Fred Cooper’s Archive).

http://www.beamish.org.uk/ (Beamish Museum).

http://www.eastdurhamheritagegroup.co.uk/ (Seaham Heritage and lifeboat centre).