D-Day's Secret Harbours

24/02/2020 | James MacDonell

In the 75 years since allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy the story has been retold many times. From harrowing accounts of the horrors of war to blockbuster Hollywood films showcasing war time heroics and even as an inspiration for fictional beach landings (2004’s Troy with Brad Pitt comes to mind) the events of D-Day are ever present in our media and thoughts. Yet, upon reflection I came to the realisation that despite this prevalence I had absolutely no idea how the allies went about creating the infrastructure in secret to land so many troops in Normandy. Nor how the troops were supplied once they were there. Where were the physical remains of the enormous pre-invasion infrastructure that was undoubtedly required? I certainly hadn’t noticed it while I’d been out and about and sometimes actually in the waters around the south coast. As it turns out I simply wasn’t looking hard enough.

This is where CITIZAN comes in. When I got the option to volunteer through my University, I thought it would be invaluable additional experience in the practical use of archaeological surveying equipment. However, while sitting in the nearby café at Stokes Bay waiting to see if the rain would pass before we could begin, I began to learn more about the seemingly innocuous concrete structures lining the shore in a story as interesting as D-Day itself.

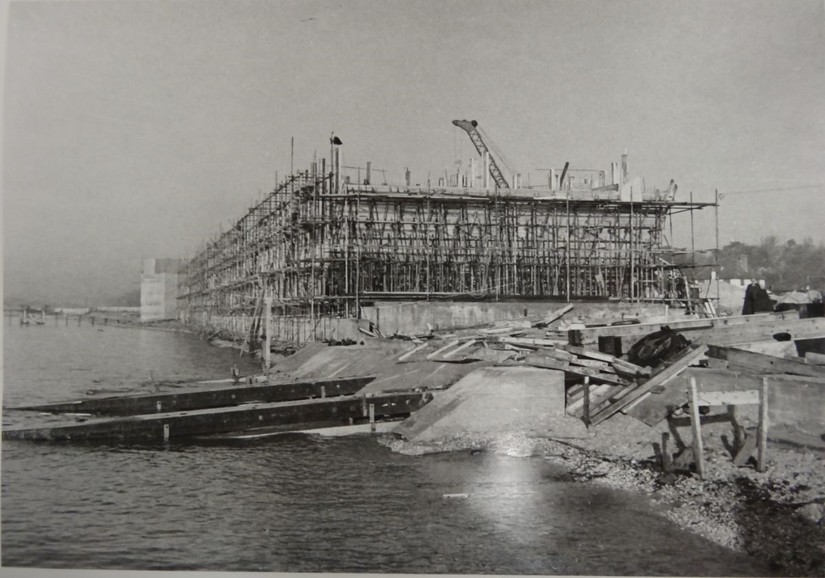

What looked like the remnants of some long-abandoned sea defences or maybe even an old parking lot slowly being swallowed by the ocean was in fact once the site of a large scale and covert operation vital to the war effort. Between 1943 and 1944 an audacious plan was carried out, across the south coast. Construction began on the components for the Mulberry harbours at Omaha and Gold beach to serve as vital shelter for allied ships during the immediate aftermath of D-Day and the initial phases of the invasion of France. However, unlike more traditional harbour constructions, these concrete components were being constructed about 100 miles away from where they were to be used. The Phoenix caissons were one product of this plan, huge concrete structures up to 60m in length and 18m in height that were constructed at sites along the south coast such as at Stokes Bay. Once completed these breakwaters were then sunk to maintain their secrecy and, when the time came, they resurfaced from the sea floor like a phoenix rising from the ashes (hence the name) and towed across the channel to form part of the Mulberry Harbours. The ingenuity of purposefully scuttling and then recovering these breakwaters along with the fact that so many worked in absolutely secrecy with such focus that the entire project was completed in a year is truly amazing.

As was discussed by a group of us while surveying these sites it’s hard to imagine a project requiring 15,000 workers and 630,000 tonnes of concrete for the phoenix caissons alone being kept completely secret in today’s digital age to the degree that three quarters of a decade later archaeologists still don’t truly understand it. The importance of these sites cannot be understated, in total the Mulberry harbours served as the landing site for 2.5 million men and 0.5 million vehicles in the vital early stages of the invasion of France. Stokes Bay also served another vital role, when D=Day finally arrived many vehicles were transported onto boats at this temporary harbour site, the concrete matting that these vehicles used to traverse the pebbly beach are unveiled at low tide, a small piece of evidence from a significantly larger operation. The components are all here for a fascinating story: secrecy, ingenuity and a united monumental human effort in a battle against evil.

However, looking at the site today it’s hard to imagine what it would have looked like only 77 years ago when this story took place. The once grand structures are no more with only the concrete floors remaining, while shingles and stones cover a vast portion of these floors (which made it frustratingly hard to find exactly where the edges of these structures were for recording purposes). The mechanism by which these breakwaters were launched into sea are long gone as is most evidence of how the construction took place. However, by recording the outlines of these sites we can begin to understand the size of the buildings, nonetheless much of the archaeological evidence is lost to us. The secrecy of the project means contemporary accounts of the operation of these buildings are extremely rare and only a few photos have been found in archives. As sea levels rise, sea defences are constructed on top of these sites, and the inevitable force of erosion continues, it’s highly likely these sites might one day disappear altogether. Having volunteered and learnt about these harbours I hope that through the data recorded these construction sites can be better understood. But I also hope that the story of how an entire harbour was constructed on the other side of the channel, then deliberately sunk, then brought back from the depths and then finally sunk again can be retold to future generations.

Though for me the story doesn’t end there, in an odd mix of fascination for what I had learnt and frustration that such an unassuming part of the coastline could hold such an enthralling story without me knowing it, I started to reflect and research what other secrets this coastline could hold. On the fieldwork I was told that one of the phoenix caissons had been wrecked in Langstone Harbour, a place where I’d windsurfed many times and yet never noticed. The next time I was there, after taking a slight detour on the way home, I spotted the wrecked caisson. How had I missed that? Even more bizarrely while conducting some research for blog post I realised I’d actually seen two of them before and simply not paid enough attention. The two caissons at Portland Harbour had simply looked like concrete structures to me when I was last there, seemingly not worthy of note. So not only is the recording of these sites vital to preserve the historical record for generations to come and to understanding these structures, but the archaeological remains of these phoenix caissons and their construction sites made me reflect on my own perception of archaeological remains. Behind these unassuming concrete structures that I had previously so readily dismissed was a fascinating story that has since enthralled me. And now, whenever I’m on the shore or on the water my perception of the coastline that I see has changed. For every chunk of concrete, weathered wall or even abandoned structure I just have to squint at them suspiciously and ask myself what secrets they hold, for the unassuming can sometimes be a gateway into uncovering a story better than any Hollywood film or best-selling book.

Further reading

https://www.portlandhistory.co.uk/mulberry-harbour-phoenix-caissons.html

https://www.maritimearchaeologytrust.org/mulberry-harbour

https://www.friendsofstokesbay.co.uk/phoenix-construction-sites/